A Network of Infrastructures: Exploring Public Libraries as Infrastructure

by Louise Rondel, Laura Henneke and Alice Corble

1 July 2019

Originally published in our Old Blog.

To mark one year of Infrastructural Explorations, this CUCR blog entry reflects on our latest Exploration, curated by Dr Alice Corble.

Since June 2018, Louise and Laura have been co-curating a series of Infrastructural Explorations in which we explore a particular infrastructure and consider its impacts on the urban landscape. During these Explorations, we invite participants to engage with their embodied and sensorial contact with the infrastructure we encounter to cultivate an ‘infrastructural literacy’ (Mattern 2013). In this, we ask how (and, indeed, if) our embodied engagements with infrastructure can attune us to questions of power and distributional (in)justice (Tonkiss 2015). We also attend to the politics of the siting of infrastructure, to its unequal environmental, social and spatial impacts and to forms of structural violence imbued in these.

Typically on these Explorations, we encounter what Lisa Parks (2015) describes as ‘stuff you can kick’: sewage plants, electricity pylons, roads, rail and tramways, underground ventilation shafts, recycling centres, incinerators. So how were we to explore public libraries as infrastructure? The shelves, the books, the computers, the cables? The ‘stuff we can kick’? Certainly. The infrastructure of libraries, but libraries as infrastructure…?

Yet, as sociologists Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey Bowker (2002) point out, infrastructures also extend to intellectual and institutional processes, including measurement standards, naming conventions, classification systems, technical protocols and bureaucratic forms. This reminds us of the guts of a library, an element that Shannon Mattern’s (2014) work builds on, by exploring the whole integrated assemblage of a library as infrastructure. She posits that thinking about

..the library as a network of integrated, mutually reinforcing, evolving infrastructures — in particular, architectural, technological, social, epistemological and ethical infrastructures — can help us better identify what roles we want our libraries to serve, and what we can reasonably expect of them. What ideas, values and social responsibilities can we scaffold within the library’s material systems — its walls and wires, shelves and servers?

And so, at 9.30am on a sunny Wednesday in May, a group of nine of us met outside Idea Store Whitechapel in Tower Hamlets. Arriving with coffee, over-sweet pastries and (of course) biscuits amongst the market traders setting up their stalls for the day, we were here to explore public libraries as infrastructure.

Idea Store Whitechapel

Alice introduces the Exploration by briefly narrating the historical context of UK public libraries in infrastructural terms. With the Royal London Hospital sprawling behind us, its blue-hued glass edifice mirroring that of the Adaje-designed library on the other side of Whitechapel High Street, connections can be drawn between the infrastructure of the NHS and the national public library service.

The UK public library national network of statutory provision in every locality is legislated by the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964, a modernisation of the original 1850 Public Libraries Act, which allowed boroughs to establish municipal libraries freely open to all classes, financed through public taxation. The ‘64 act is a product of the ‘welfarist spirit’ of early to mid-20th-century public library development. Explicit and sustained efforts were made to establish a ‘national grid’ of quality provision for all, based on a blueprint conceived by Lionel McColvin at the same time as the 1942 William Beveridge report which laid the foundations of the welfare state (Black 2000, 2004).

From the neoliberal political settlement of the late 1970s onwards, however, this infrastructure has become gradually eroded, and the past decade of austerity has seen an accelerated splintering of the network into increasingly impoverished and disarticulated forms of provision. In 2014 William Sieghart was commissioned by government to conduct an independent review into the crisis facing public libraries in which he likened the situation to a ‘Beeching moment’, referring to the drastic cuts to the national rail network in the 1960s.

In London, the picture of statutory public library provision can be described as a postcode lottery, with some boroughs holding on to council-run services while many others have become outsourced to volunteers, social or commercial enterprises to run and many branches closed.

The library Exploration guided by Alice traverses three London boroughs. Beginning with Tower Hamlets, whose borough council re-designed and branded its libraries as ‘Idea Stores’ in the early 2000s in an effort to make the borough’s libraries much more accessible to diverse communities and integrated with digital and adult education infrastructures, we wander around Idea Stores in Whitechapel and Watney Market (Shadwell). We then cross the river (via the Overground) to Southwark where we visit Canada Water Library (designed by Piers Gough and opened in 2011) and consider its urban context in the regenerated Docklands area. For our final leg of the exploration we travel further south (via Canada Water station upon which the library is built) to New Cross Learning in Lewisham. This is a community branch library which has been run by volunteers (with Lewisham Council providing book stock and circulation systems) since 2011 when local government cuts meant the library would otherwise close.

Exploring these libraries in the context of austerity and a reduction in spending on public services coupled with the increasing demand on what libraries can and should do, we want to consider how our embodied encounter with public libraries enable us to foster Mattern’s ‘infrastructural literacy’? These reflections from Louise’s fieldnotes highlight how corporeal experiences can sensitise us to the workings of overlapping infrastructures and, indeed, the public library as infrastructure:

Going inside Idea Store Whitechapel at 9.45am, I am surprised at how busy it already is. People are leafing through newspapers or working studiously on the shared tables, earphones in, exercise books open, a pile of pens and highlighters alongside them. More people occupy the computer stations, using the internet to read the news, write essays or watch youtube videos.

A little further down the road in Idea Store Watney Market, the library is equally as busy. I find a chair looking out over the main road and the entrance to the market and tune myself into the soundscape: the ping of the lift, hushed voices, the tapping of laptop keys, shifting bodies on the faux-leather chairs above the low rumble of traffic from the constantly-busy road outside, occasionally a siren pierces the near-silence. Despite the busy market outside the main entrance and the flow of cars, lorries and buses, very little noise from the outside penetrates the library, it provides a quiet haven for concentration, reading, studying, sitting.

(Fieldnotes, Louise)

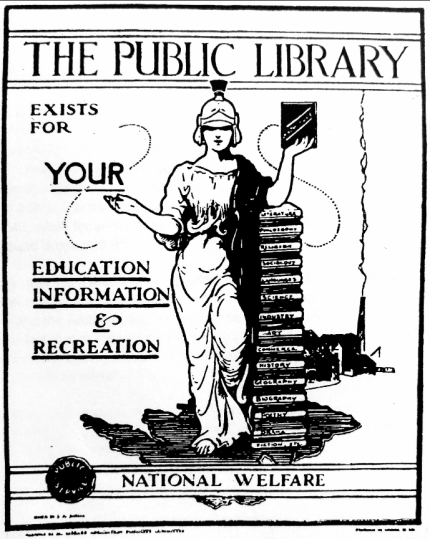

Idea Store Watney Market

Views from Ideas Store Watney Market (Photos: Laura Henneke and Louise Rondel), and Rupert and Laura find a copy of George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier including historical images of Stepney and Shadwell (Photos: Alice Corble).

Canada Water Library

By the time we reach Canada Water library, I am desperate for the toilet, tired and my phone battery is low. Inside the library I use the bathrooms, sit down in the cafe and find a plug socket to charge my phone: important infrastructural provisions which are difficult to access for free in urban spaces increasingly designed around consumption or dominated by defensive architecture.

Through my corporeal experiences, I am become attuned to what the library offers: a quiet space, a (internet-)connected space, a space for sitting and recharging, for reading, or studying, or doing nothing; the library as infrastructure.

(Fieldnotes, Louise)

Essential urban infrastructures at Canada Water Library, and Red Box Project’ donations box for women and girls experience ‘period poverty’ (Photos: Louise Rondel and Alice Corble).

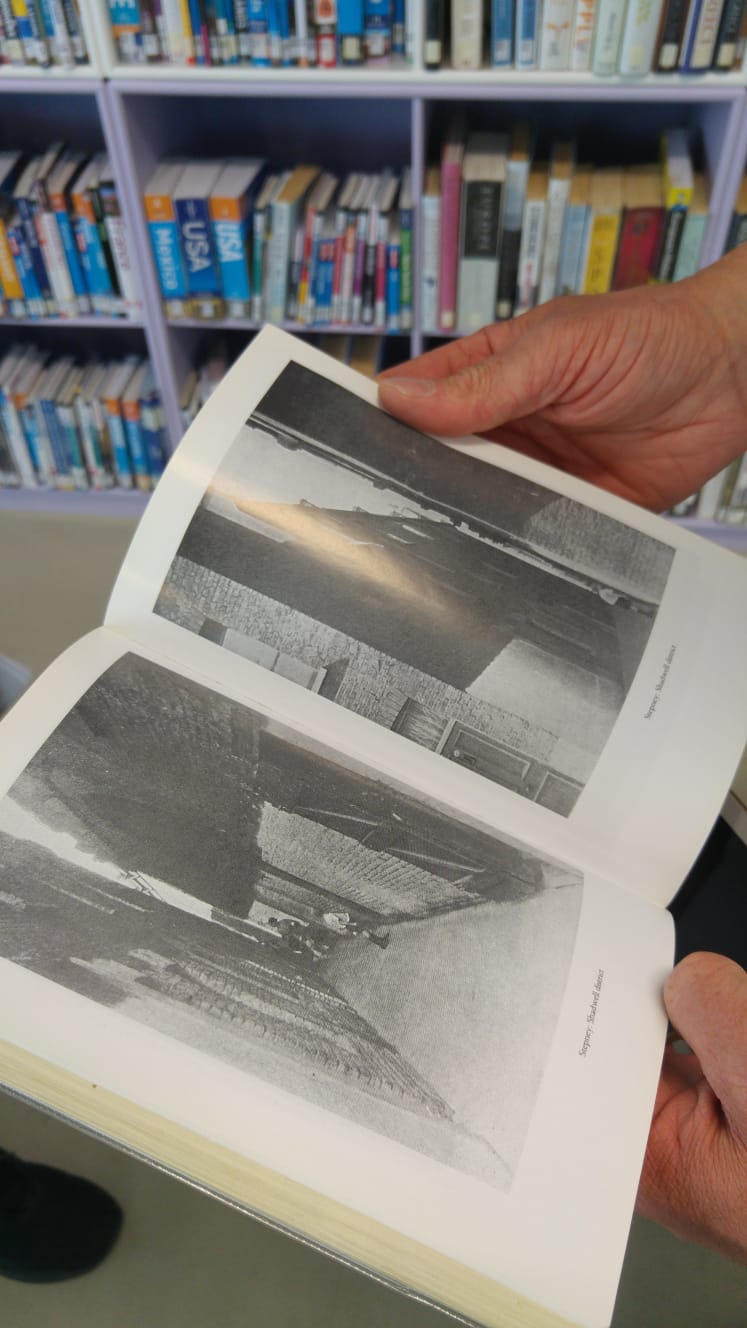

Annotated map (Photo: Louise Rondel), and Infrastructural Explorers linger outside Canada Water Library (Photo: Alice Corble).

Infrastructural Explorers reflect above the central spiralling void of Canada Water Library (Photos: Alice Corble).

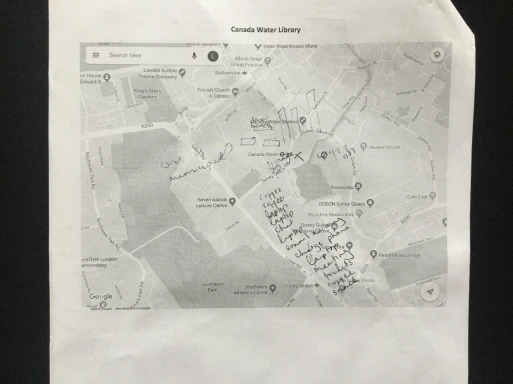

Images of the former working docks form a backdrop to books on social sciences at Canada Water Library (Photo: Alice Corble).

As well as developing an ‘infrastructural literacy’, of our Explorations we also ask ‘but then what? What might happen after all the touring and mapping, the listening and smelling, the playing of games?’ (Mattern 2013). What do we then do with this? What else could these bodily encounters enable?

New Cross Learning

As we move to New Cross Learning, the final stop on the Exploration, the answers to these questions become clearer.

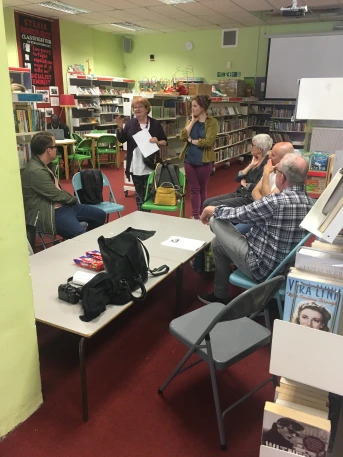

Last stop: New Cross Learning, a volunteer-run library (Photos: Laura Henneke).

Gill Hart and Kathy Dunbar, the activists who ran the campaign in 2011 to save New Cross Library and have been running it as managing volunteers on a daily basis ever since, tell us about the ongoing struggles to keep the space and service afloat and meet the needs of its diverse users. Unlike the libraries we have seen in Tower Hamlets and Southwark, which despite reduced budgets are still fully professionally staffed and resourced by council employees and equipment, the infrastructural practices that keep the majority of Lewisham’s libraries going are precarious and voluntary, powered by necessity, care and an activist ethic of resistance.

As one of our Explorers describes:

“Celebrate working class women in struggle” read the banner hanging on the back wall of the New Cross Learning library. Sitting on the children’s chairs with a mug of tea chatting with the Goldsmith’s Infrastructural Exploration group, may not have looked like such a celebration but the fact that we were able to visit a lively, functioning library at all, certainly deserved one.”

(read Jonny’s full text here)

Here the space to sit and read or drink tea cannot be taken for granted. Through our embodied encounters in New Cross Learning, the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructures that sustain the library are foregrounded. We become attuned to the labour of maintenance and care which enable people to freely enter into and use the space; labour which is not only not to be taken for granted but which is, in Jonny’s words, to be celebrated. What’s more, in the services offered in this otherwise unremarkable cuboid building (before it was a municipal library it was a Co-op supermarket) are numerous :- appointments with the Lewisham Credit Union, a space for community and political meetings, children and family activities, free-to-use computers or assistance in navigating increasing online bureaucracy to name but a few. The library as infrastructure becomes apparent, not just ‘stuff you can kick’.

New Cross Learning volunteer manager Gill Hart talks to the Infrastructural Explorers (Photo: Laura Henneke).

As Simone (2004) highlights, the concept of infrastructure not only belongs to ‘hard’ systems such as reticulated networks of highways, pipes, wires or cables, but can also extend to the ‘softer’ but no less impactful conjunctions of people’s activities in the city. ‘People as infrastructure’, as Simone calls it, manifest in contexts where municipal or corporate provision has been withdrawn, and complex ‘bottom-up’ alignments between objects, spaces, persons and practices compensate to facilitate communal survival and development. Building on Simone’s work, Tonkiss considers such urban infrastructural practices in terms of ordinary labour activities such as talking, listening, sharing, caring, lending, tending, cleaning, and carrying: ‘the soft infrastructure of sociality that mediates and holds the collective lives of strangers and near strangers’ (Tonkiss 2015).

In the case of New Cross Learning, such soft infrastructures are made of empathetic practices and relations generated by the way in which both library volunteers and library users share a similar habitus: the conditions of austerity that bring them together as fellow citizens finding ways to live in solidaristic yet precarious spaces of survival.

But what then? Libraries are well known as spaces of literacy, but a greater ‘infrastructural literacy’ is needed to understand how they are situated within wider ecologies and economies of vital urban and civic infrastructure. This Exploration has offered a glimpse into the manifold ways in which libraries work through complex networks of intersecting practices, parts and publics that hold them together and keep them going, despite uneven geographies of statutory distribution of resources.

Postscript:

Our visit to New Cross Learning concluded with a tour of a little-known underground archive of objects and ephemera in the basement, owned and catalogued by the volunteer-run Lewisham Local History Society who meet there weekly. Sara, one of our Explorers, notes: “I can’t imagine any organisation other than one run by volunteers storing such a host of treasures. The fact it exists is a testament to Kathy and Gill’s belief that NXL is of and for the community.” This cornucopia of hidden treasures would have been lost without their saving of the library, and our infrastructural Exploration of it yielded so many thoughts that warrant their own separate blog post, so watch this space….

Archived ephemera by the Lewisham Local History Society, and smelted glass of the original Crystal Palace (Photos: Laura Henneke).

Sara: I never got to look inside the box in the photo as we all congregated to marvel at the smelted glass of the Crystal Palace. The box above was so light that it felt empty, so presumably it did just contain a list – I wonder what was on the list? (Photo: Sara Wall).

Join us for the next Infrastructural Exploration on July 26th in Beckton, East London. To sign up and for more info click here.

The Infrastructural Explorations are generously supported by the Centre for Urban and Community Research (Goldsmiths, University of London).

Louise Rondel is a PhD candidate in Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. She is researching London’s beauty industry and its vibrant materialities to examine the co-constitutive relationship between bodies and cities.

Laura Henneke is a PhD candidate in Visual Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. With a background in Urban Design and Architecture, she researches the visible and invisible impacts the Belt and Road Initiative has on the cities it connects.

Dr Alice Corble is Associate Lecturer and Research Assistant in Sociology at Goldsmiths. She has eight years’ professional and voluntary experience working in a range of different libraries. Alice was recently awarded her PhD in Sociology from Goldsmiths, University in London, titled ‘The Death and Life of English Public Libraries: Infrastructural Practices and Value in a Time of Crisis’. Her thesis is available here for those interested in further reading on the topic.