Food Poverty and Charity in the UK: Food Banks, the Food Industry and the State

A Report by Pat Caplan

19 June 2020

Originally published in our Old Blog.

What does food poverty mean to you?

- Not having enough to eat, being malnourished, being hungry?

- Not being able to eat foods which you want or which are good for your health?

All of these are part of definitions of food insecurity or food poverty.

Isn’t this just a part of being poor?

Yes and no. If you are poor (i.e. you have an income of less than 60% of the average) you are also likely to be food poor.

But because food is the most ‘elastic’ part of the household budget, you may have to skimp on food to pay for other essentials such as bills, council tax, rent. You prioritise these because not paying them can lead to eviction and becoming homeless, having your gas or electricity cut off, or the arrival of the bailiffs.

By the time I started my research on food poverty in the UK in 2014, it was already widespread and has continued to grow inexorably since that time, with a quantum leap after the advent of the pandemic and the ensuing lockdown.

So how has UK society responded to this situation?

One response has been the growth in food aid organisations, particularly food banks. The Trussell Trust, set up in 2000, now has 1200 branches, while there are some 800 independent food banks, so at least one in every town, more actually than McDonalds.

How do they work? Within food aid organisations, there are several categories of players: donors, volunteers (including trustees as most are charities) and, of course, clients.

Donors are members of the public who drop a tin or package into the collection bins in supermarkets or they are members of schools, churches, synagogues and mosques who raise collections for their local food bank.

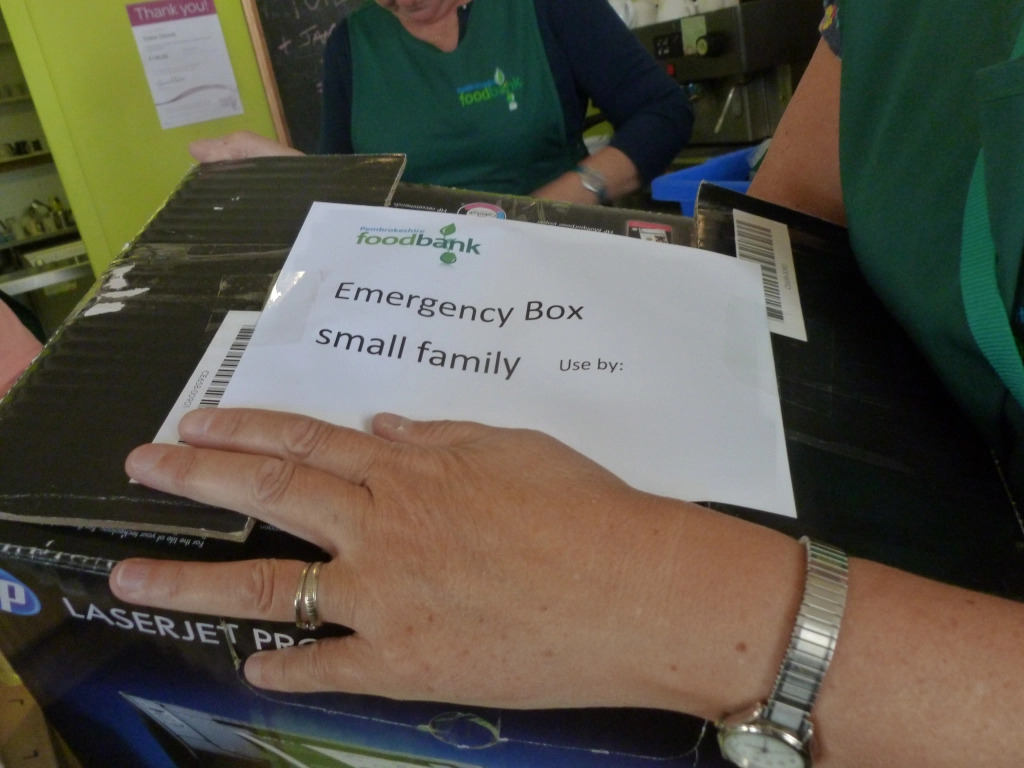

Food banks provide food parcels to clients, often on production of a voucher obtained from a professional agency like Citizens Advice, GP, teacher, social worker. But this help is not unlimited – Trussell Trust for example, sets the limit at 3 times in 6 months. Furthermore, most of the food is ambient – tins, packages, bottles; only recently have some food banks been able to supply any fresh food like fruit and vegetables.

Food banks are primarily run by volunteers who collect donated food from supermarkets and elsewhere, sort it by type and date, store it and make up parcels for clients. It’s very labour intensive but there is a whole army of people who participate on a regular basis.

More recently, donors have also included the food industry which donates ‘surplus’ food to charities: dented tins, squashed packages, food that is nearing its ‘consume by’ date. Much of this passes through food collection charities such as Fareshare, which works nationwide, or the Felix Project, which operates in and around London. The increasing participation of the food industry has enabled more fresh food to be available to food banks, but supplies are by no means guaranteed. Participation in the work of food charities enables the food companies to claim that they are fulfilling their corporate social responsibilities and thereby improve their ‘brand’.

In my research I interviewed many volunteers and even participated in some of their meetings and tasks. Many expressed their dismay about food poverty and felt that they should ‘do their bit’ to alleviate it. However, fewer volunteers were willing to become activists and seek to challenge the situation from which it arose, although more recently, some organisations like Trussell have engaged in a greater degree of campaigning.

Clients for the most part have an ambivalent attitude to food charities. On the one hand, the food parcels they receive help to alleviate some of their needs, but this comes with a heavy price: lack of choice and a feeling of stigma which is often internalised. Only a minority of food banks encourages clients to become volunteers, thereby breaking down the divide between givers and receivers.

Research on food charities suggests that only a minority of the food poor visits a food bank, yet the growth of this sector is a witness to the increasing need of many people. Why is this happening?

- Low wages and precarious employment

- Low benefits, plus long waiting times to access Universal Credit

- Cuts in benefits

It can be summed up as low income, insufficient to meet all needs.

The fragility of the charitable response to food poverty has been exposed by the pandemic which has seen unprecedented numbers seeking help.

This problem cannot be solved by food banks – it is the result of historically-specific government policies such as austerity and therefore needs significant structural change to ensure that all citizens have sufficient income to feed themselves and their families.

Read more about Pat Caplan’s research on Food Poverty and Food Aid in the UK.

Pat Caplan is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London, where she previously taught for 25 years. Pat has also researched food issues in south India and Tanzania. In the 1990’s she directed a research project on public understandings of the relation between food and health, with the London Borough of Lewisham providing one of the focus areas. This material is now on the National Archives web.

︎ Images by Pat Caplan.