“Stitched With Love”: Caring For and Staying With Tactile Stories

by Phavine Phung

9 December 2022

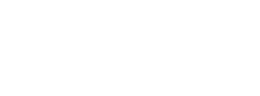

In recent years, we have seen the rise of participatory textile making featured in research activities as the subject of inquiry, means of investigation and a way to communicate research (Shercliff and Holroyd 2020). In 2021, I ran a project called “Stitched with Love”, a collaborative quilt making project that is part of my PhD. The project involved a community of cross-national families who were separated due to the hostile UK family migration rules. I mailed scrap fabric to families who were interested in getting involved; they employed drawing, stitching and writing to narrate their experiences as they lived through the immigration process. The scraps were then mailed back to me to be stitched together into a quilt.

These panels tell stories through written words and delicate objects. As I was stitching these panels, the slowness of the activity helped me contemplated certain ideas, particularly around the concept of “caring for” and “staying with” the stories told through these panels.

In The social life of things, Appudarai (1986) tells us that artifacts often have long and complex biographies. Objects acquire meanings and evoke memories through their associations with the people who have owned them, or through whose hands they have passed. The fabric scraps had traces of histories from other projects. Before forming into one whole piece, the quilt blocks had their histories somewhere else, in the participants' homes. They “hold” the stories, or to use the words of Hockey (2014), these quilts “bear witness” to the lived experiences of those we collaborated with (p.102). So given that the objects that we are handling, like quilts, are vested with histories and biographies of their own, what are we to do with them? How do we care for them?

Matt Ratto (2011) argues that making can engender caring for something, rather than simply caring about. He proposes that we think about caring “not just in terms of feeling but also in terms of applied, responsible work” (p.258). The point here is that caring for means to see oneself as part of the issue, thus being partially responsible (Lindstrom and Stahl 2016, p.74). When I received the quilt blocks back from the participants, I found myself asking: how do I materially give these stories structure and support? How do I display these stories? Sewing all the blocks together took a lot of planning but sometimes also improvisation. Since each block contains writing and objects, it was essential that after sewing together, the words were not overlapping and the objects were clearly and securely displayed. This involved a repetitive process of measuring, trimming away and adding fabric. The fabric is made of very diverse materials so sewing them required a lot of time and learning to work the different settings on the sewing machine. Some making aspects went beyond what a sewing machine could do, for example, putting the backing together. In that case, I employed hand sewing. One way we can honour the stories shared through these materials is by being attentive to the materials.

Since this making process was very slow, I was also able to read, touch, and feel the stories for an extended period of time. The slowness of it all allowed me to stay with the stories and the mess of research (Jungnickel 2018). Lindstrom and Stahl (2016) argue that staying with “means not to rush to solutions or to resolve problems, but to stay with something, with complexities, mess and troubles” (p.72). I experienced literal mess in my own room with piles of fabric in one corner, loose colour threads on the floor, etc. These tangible messes were easy to identify but there were also intangible messes.

Cook (2009) states that “the ‘messy area’ is formed where participants have deconstructed well-rehearsed notions of practice and aspects of old beliefs, [and] are aware of the dawning of the new, but as yet not made sense of it” (p.281). To put it simply, the messy area is the space between the already known and the “nearly known”. To illustrate this point, let us look back at the sewing process. In putting the story panels together my mind predominantly focused on the technical aspects of sewing. I had a general idea of the participants’ stories since I read them as I was sewing but I could not articulate their meanings or engage with the intricacies of their stories at that point in time. I could not decode anything, not until all the blocks were sewn together into one piece; therefore, I stayed in that messy space between “the already known and the nearly known” for an extended period of time. That space was uncomfortable, mainly due to the length of time I had to be in it. However, looking back, I appreciated that space since it taught me to be patient and to suspend my hurriedness to immediately dissect and analyse what is in front of me.

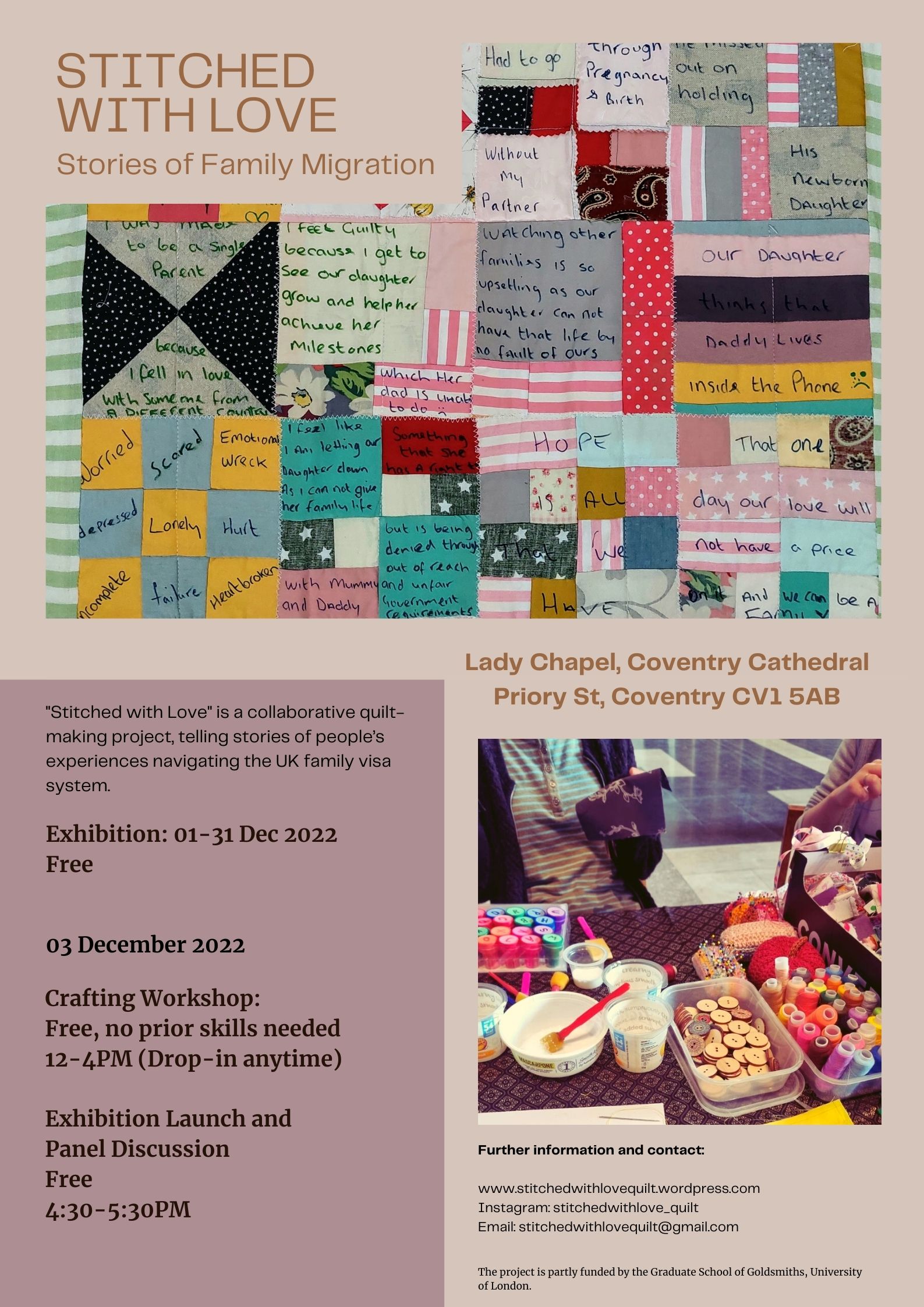

After a whole year of putting these panels together, the project produced three quilts. There is an exhibition, featuring these three quilts at the Lady Chapel of Coventry Cathedral. The exhibition is open to the public from 01-31 December 2022. On the 3rd December, we ran a drop-in crafting workshop, which aimed to bring people together to share experiences or learn from other’s experiences of immigration while stitching a quilt. The workshop provided a slow-paced atmosphere where participants could create and share stories. This was followed by a panel discussion, which included speakers who have personal experiences with the UK family visa system and immigration practitioners from local organisations. The panel served as a space to share and discuss the experiences of navigating the family migration rules.

Notes:

Appadurai, A. (1986) The social life of things: commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cook, T. (2009) ‘The purpose of mess in action research: building rigour though a messy turn’, Educational Action Research, 17(2), pp. 277–291.

Hockey, J. (2014) ‘The social life of interview material’, in C. Smart, J. Hockey, and A. James (eds) The craft of knowledge: experiences of living with data. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jungnickel, K. (2018) ‘Making things to make sense of things: DIY as research and practice’, in Sayers, J. (ed.) The Routledge companion to media studies and digital humanities. New York: Routledge, pp. 492–502.

Lindstrom, K. and Stahl, A. (2016) ‘Patchworking ways of knowing and making’, in J. Jefferies, D.W. Conroy, and H. Clark (eds) The handbook of textile culture. London: Bloomsbury Press.

Ratto, M. (2011) ‘Critical making: conceptual and material studies in technology and social life’, The Information Society, 27(4), pp. 252–260.

Shercliff, E. and Holroyd, A. T. (2020) ‘Stitching together: participatory textile making as an emerging methodological approach to research’, Journal of Arts and Communities, 1-2(10), pp. 5-18

Phavine Phung a PhD candidate in visual sociology. Her research interest focuses on using crafts to enquire into the issues of immigration and family.

She tweets @PhavineP

︎ Images by Phavine Phung