The Blue Biro Blues

by Steve Hanson

28 November 2022

I was in London. I looked at Twitter and noticed Housmans were selling off some of Doreen Massey's books, who had just died. I knew they had sold some of Stuart Hall's, two years previously, but I missed that sale.

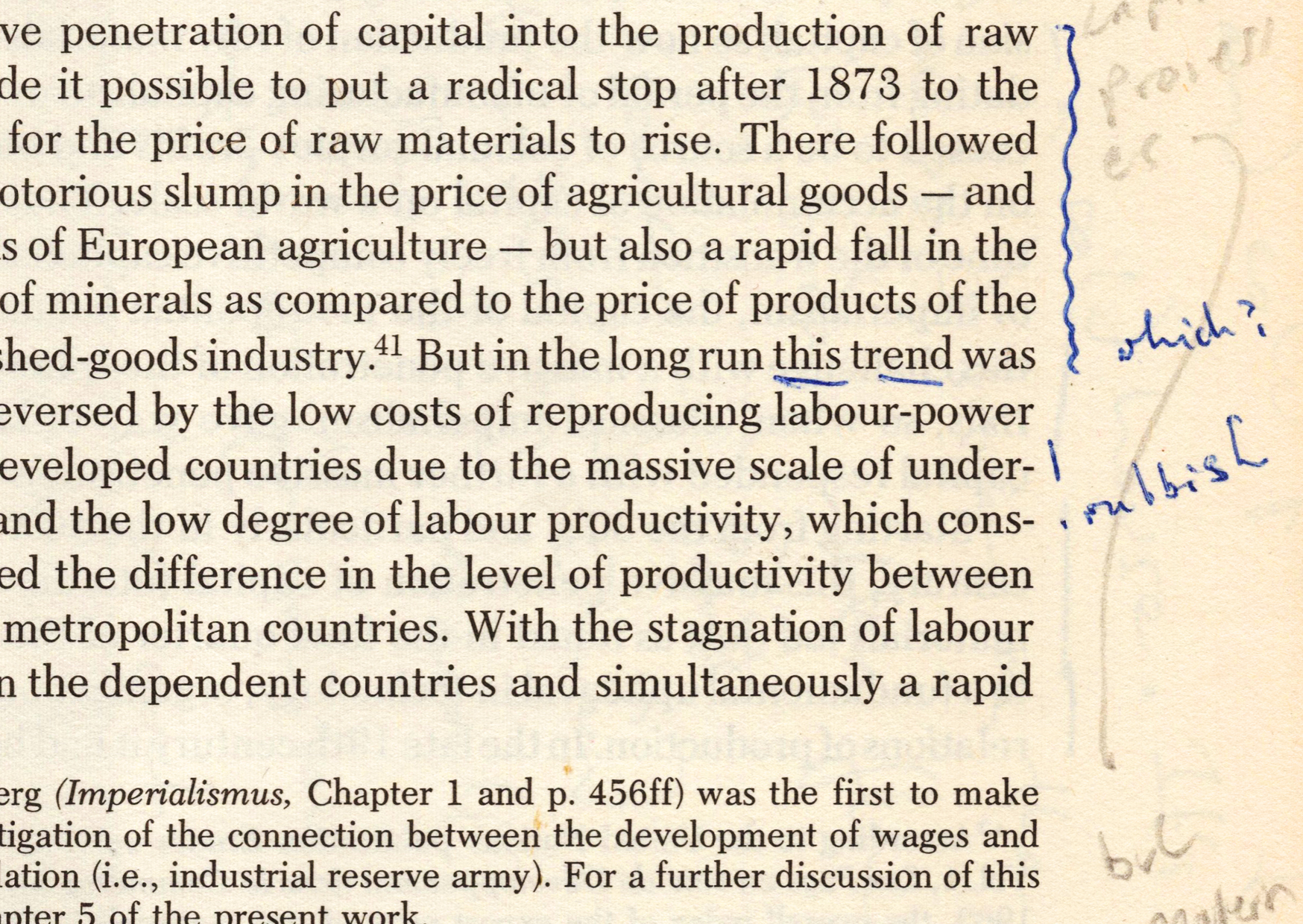

I got on the tube and went straight up to King's Cross. I bought Mandel's Late Capitalism and Nicos Poulantzas's Political Power and Social Classes, both in their New Left Review editions, beautiful hardbacks, with silver embossing. They were a couple of quid each. They all had writing in them, in Doreen's hand. I got some other academic books. I also bought a History of Wythenshawe that had belonged to Massey, because I live in Manchester. I have since met the artist Simon Woolham, who told me that the Massey family were neighbours in Wythenshawe, when he was growing up, and that Doreen was occasionally his babysitter.

I went through the books and wrote notes. I have much more to say about that experience later – and the material - but most immediately I was cheered to see that Doreen was as spiky a reader as I am. There is nothing like a Massey flat diss in blue biro to cheer you up. We should resist the pompous authoritative tone, if what is being said makes no sense.

And students should see this, so I feel a little conflicted about owning these books. Massey was an extremely important academic. In some alternative moral universe, I shouldn't really own them. They are tucked away in a private home, but I'm also a hopelessly addicted collector. All of this is 'very Massey.’ The space the books now exist in - the shelf on which the books sit - is not a neutral container. It has ownership. It has a politics. It has a particular relation to access. They are now resources for someone again, not for all.

If universities weren't so compromised, in terms of their status between the public and the private, I'd donate these books to a relevant archive. In this parallel moral universe (which doesn’t actually exist) it is where they should be.

The same goes for the Stuart Hall books, if they were annotated. The International Anthony Burgess Centre in Manchester used to sell copies of Burgess’s novels to the public from Burgess’s own collection. But these were mint 1970s or 1980s copies straight from the printer, which had accumulated in whichever Burgess home: none of them were annotated. This is very different.

I also have letters and postcards from Jeff Nuttall, and photographs of him, which should really go to Manchester University’s John Rylands, which has the bulk of his archive. But the same issue applies: who can guarantee that they won't be sold off to a private collector down the line, once they have been handed over, because of some crisis, and no doubt at root yet another crisis of capital? We have learned what happens to libraries in England during times of crisis. We have learned what mendacities the university as a privatised managerial space is capable of. So, I hang on to these objects, hoping for stronger public institutions in the future. A futile desire, I think.

But I am also acutely aware that I have material that can be turned into cultural capital, via the insights that can be made through them. As Roger Burrows wrote about the culture of the REF, paraphrasing the HBO TV series The Wire, you either ‘play or get played.’ I understand this all too well. I have left things lying around in the open and have been played before. I hate this situation, but it is real.

But all of this is how cultures of privatisation poison our societal relations right to the roots, and as someone who collects – a bourgeois pursuit if there ever was one - I am to an extent complicit. Under this logic everything becomes society, gesellschaft, not community, gemeinschaft, in a kind of horrible, magnetic checkmate. I wish it were otherwise. I have tried for as long as I can remember to resist this logic. Here is a line from Adorno’s Minima Moralia which always stuck with me:

‘People who belong together ought not to keep silent about their material interests, nor to sink to their level, but to assimilate them by reflection into their relationships and surpass them.’ (1997: 45).

I would love to believe that we can all ‘assimilate our material interests by reflection into our relationships and surpass them’. But it’s difficult, nigh on impossible, because our lives are woven into the everyday, routine deceits of competition and the life of the private individual. When we are forced to navigate and move forward on an economic base, how can we resist this corruption of material interests? The logic of privatisation and competition saturates everything now. I know because I have spent a long time being far too naive and idealistic about all of it. Attempting to overturn this logic as a single individual, one merely becomes the volunteer loser. You become, in fact, Canute. Adorno would barely be able to breathe the air in the cultural world of the twenty-first century.

These books, just as objects - before we even get into their content - throw us into the world as Doreen Massey understood it. A world in which space and the things in it have agency, because they are situated in often invisible networks of power which - like gravity moving entire planetary systems - determine the movements of our lives far more than we can ever imagine.

But the traces people leave, scribbles in margins, and our memories of them, they lie in the landscape like unexploded ordnance: evidence of more agonistic and communal ways of being that I hope might explode again.

Notes:

Adorno (1997, orig., 1951) Minima Moralia – Reflections from Damaged Life. London: Verso

Burrows (2012) 'Living with the h-index? Metric assemblages in the contemporary academy' in The Sociological Review 60 (2), pp. 355-372.

Steve Hanson is a writer, researcher and lecturer. He completed his MA at the CUCR before going on to a PhD in Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London.

He tweets @yesitizess

︎ Image by Steve Hanson